1. Why 2026 Cannot Look Like Any Other Year

2026 is not a reset year.

It’s a decision year.

For much of the Caribbean, the instinct has always been to wait — to assume that the next budget, the next election cycle, the next oil discovery, or the next global rebound will ease the pressure and return things to “normal.”

But what we’re experiencing now is not a temporary squeeze.

It’s a structural shift.

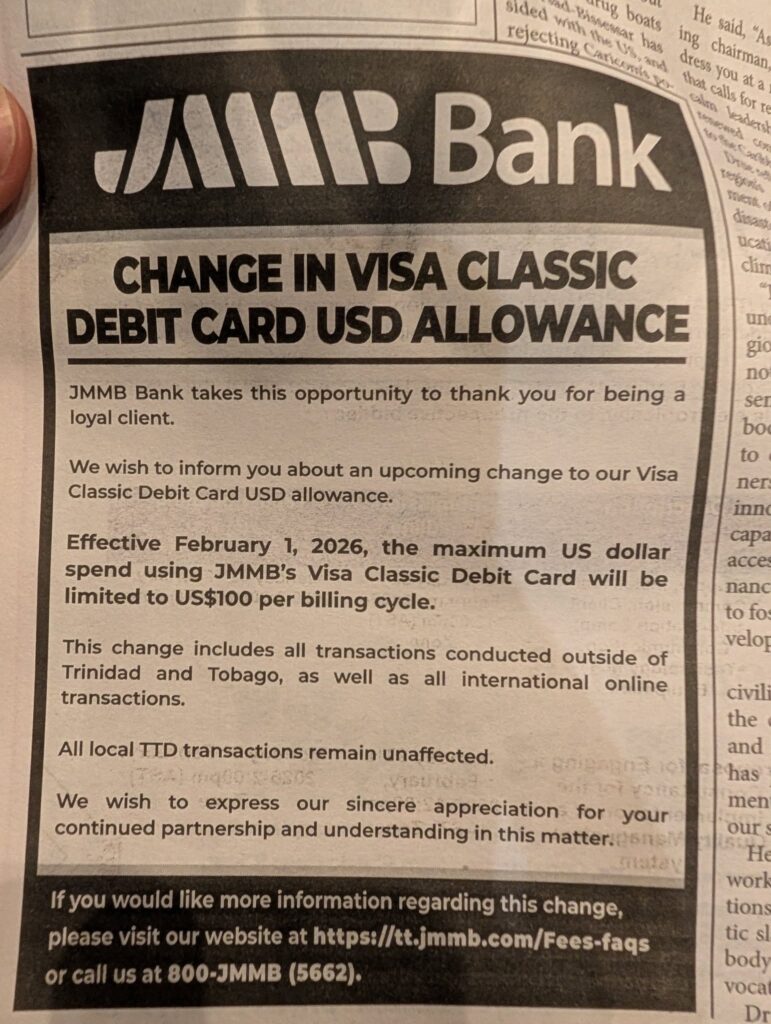

Foreign exchange pressure across the region is no longer episodic — it’s persistent. Banking limits on USD access are tightening, not loosening. Geopolitical tensions are spilling into global trade, payments, and capital flows in ways that disproportionately affect small, import-dependent economies. These forces are reshaping how money moves, how business is done, and who gets access to opportunity.

Recent USD restrictions by local banks should not be read as isolated decisions or short-term adjustments. They are signals — signals that the existing economic model is under strain, and that business as usual is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain.

This moment requires honesty.

We cannot assume that governments will “fix” the economy quickly.

We cannot sit back and wait for new energy discoveries to solve our foreign exchange challenges.

We cannot rely on tourism or traditional exports alone to absorb the next generation of workers or generate the USD required to keep modern economies functioning.

None of this means the Caribbean is out of options.

It means the old options are no longer sufficient on their own.

The global economy has already shifted toward skills, services, and digital value creation. The only real question left is whether Caribbean citizens and institutions choose to adapt deliberately or are forced to adapt reactively under greater pressure later.

The world has changed — and our economic playbook must change with it.

Article Roadmap

1. Why 2026 Cannot Look Like Any Other Year

Sets the context for why this moment is different — and why waiting for “normal” to return is no longer a viable strategy for Caribbean economies or citizens.

2. The Real Constraint: Foreign Exchange, Not Talent

Reframes the national conversation by explaining that the core challenge isn’t skills or effort, but how foreign exchange flows into and through small economies.

3. Why Physical Products Are High-Friction Exports for Caribbean SIDS

Breaks down the structural limits of manufacturing and goods exports for island economies, without dismissing their importance.

4. Digital Skills as Exports: The Lowest-Friction Path to Forex

Introduces skills and digital services as exports that scale faster, cost less to deliver, and bypass many of the constraints faced by physical goods.

5. Global Proof: How Countries Scaled by Exporting Skills

Examines how countries like India, the Philippines, and Estonia used skills and digital services to grow foreign exchange and resilience.

6. The Skills That Generate Forex in 2026

Outlines the specific skill fields in global demand, anchored in WEF and Coursera data, that Caribbean professionals can realistically pursue.

7. Clearing the Confusion: “But We Can’t Get Paid”

Addresses the common misconception about international payments and clarifies where the real friction exists in the Caribbean system.

8. How Caribbean Professionals Receive Payments in 2026

Provides a practical overview of the tools, platforms, and account structures used to receive international income.

9. Living in the Caribbean, Earning Globally

Explores how digital skills make it possible to stay rooted locally while accessing global income opportunities.

10. From Skill Confusion to Strategic Direction

Introduces a structured approach to choosing skills deliberately, avoiding random upskilling and wasted effort.

11. The Most Scalable Export the Caribbean Has

Closes by reframing people — not products — as the region’s most powerful and resilient export in the modern economy.

2. The Real Constraint: Foreign Exchange, Not Talent

When economic pressure builds in the Caribbean, the conversation almost always turns to effort, productivity, or skills.

We’re told we need to “work harder,” “be more competitive,” or “be more innovative.”

But that framing misses the real constraint.

For small island economies, foreign exchange is the choke point.

Domestic markets across the Caribbean are small by definition. Even the most successful local businesses quickly hit a ceiling because there are only so many customers to serve. Growth, therefore, has always depended on exporting — on earning income from outside our borders and bringing it home.

At the same time, modern life in the Caribbean is deeply import-dependent. Food, fuel, medicine, technology, vehicles, software subscriptions, spare parts — all require USD. When foreign exchange is abundant, this dependency is invisible. When it tightens, it becomes impossible to ignore.

This is why FX pressure is felt so quickly and so personally.

When USD access tightens, businesses struggle to restock or expand. Prices rise. Projects stall. Households feel it at the supermarket, the pharmacy, and even when paying for basic digital services. What looks like a banking issue or a policy decision quickly turns into a daily cost-of-living problem.

To move this conversation forward, one critical distinction must be made — and made clearly:

Generating income is not the same as receiving payment.

Receiving payment is not the same as accessing and using foreign exchange.

These are three separate systems, and in the Caribbean they do not always align.

Many Caribbean professionals are capable of generating income from global clients. People are getting paid every day for services delivered remotely — from design and consulting to software, marketing, and operations. Incomes are earned, and payments are often received in USD or other foreign currencies.

The friction appears after that point.

Local banking systems, exchange controls, correspondent banking losses, and card-based spending limits make it difficult to use foreign exchange efficiently once it enters the system. This creates the illusion that the problem is earning or being paid, when in reality the issue is how foreign exchange is accessed, retained, and circulated locally.

This distinction matters because it changes the solution.

The Caribbean does not suffer from a lack of skill, creativity, or ambition.

It suffers from economic systems that are not aligned with modern, global income flows.

Until we address that mismatch — by designing income strategies that work within existing constraints — foreign exchange pressure will continue to shape everyday life, regardless of how talented the population becomes.

Understanding this reality is the foundation for every strategy discussed in the sections that follow.

3. Why Physical Products Are High-Friction Exports for Caribbean SIDS

Manufacturing and physical exports have always played an important role in Caribbean economies — and they will continue to do so. This is not an argument for abandoning production, industry, or value creation through goods.

It is, however, an argument for being honest about structural limits.

Small Island Developing States (SIDS) face a set of constraints that make exporting physical products fundamentally different from exporting services. These constraints are not the result of poor decision-making or lack of effort. They are the result of geography, scale, and global trade realities.

The first challenge is distance.

Caribbean economies are physically far from their largest consumer markets. Every product exported must cross oceans, pass through ports, clear customs, and be insured against delays, damage, or loss. These costs are not marginal — they compound at every stage of the supply chain.

The second challenge is scale.

Manufacturing becomes competitive when production volumes are high enough to dilute costs. Small populations limit domestic demand, which means most Caribbean manufacturers must import raw materials at relatively high unit costs and export finished goods without the benefit of large, predictable shipping volumes. This creates what can be thought of as a “double penalty”:

- Raw materials, machinery, and inputs must be imported first, increasing production costs before any revenue is earned.

- Finished goods must then be exported, often on thin or irregular shipping routes that keep freight rates high.

This is a structural disadvantage — not a management failure.

Climate exposure adds another layer of risk. Hurricanes, flooding, port disruptions, and insurance premiums all disproportionately affect island economies. Even well-run manufacturers face interruptions and cost spikes that businesses on large continental landmasses simply do not.

There is also a foreign exchange dimension that is often overlooked.

Manufacturing in small economies tends to be import-intensive. Machinery, spare parts, packaging, fuel, and many intermediate inputs are sourced externally and paid for in USD. This means that even when goods are exported successfully, a significant portion of the revenue earned flows straight back out of the country to pay for imports.

Margins are squeezed from both ends.

None of this means manufacturing is impossible or undesirable. It means that, for SIDS, manufacturing is capital-heavy, slow to scale, and highly sensitive to external shocks. It is not well suited to absorbing large numbers of workers quickly, nor is it an efficient way to generate widespread, distributed foreign exchange earnings across a population.

This is the key distinction.

Physical products move through ports, ships, and supply chains that amplify cost and risk. Skills and digital services move through networks that largely bypass those constraints.

Understanding this difference is essential — because it explains why simply “doing more manufacturing” has not solved foreign exchange pressures in the past, and why relying on it alone will not solve them in 2026 or beyond.

The question is not whether the Caribbean should produce goods.

The question is what type of exports scale fastest, cost least to deliver, and generate the most resilient foreign exchange inflows under the constraints we actually face.

That question leads directly to digital skills and services — which is where the next section begins.

4. Digital Skills as Exports: The Lowest-Friction Path to Forex

Once the structural limits of physical exports are understood, the alternative becomes clear.

Digital skills and services operate under an entirely different economic logic.

When a Caribbean professional delivers a service digitally — whether it’s software development, data analysis, design, consulting, or operational support — no physical product needs to move. There are no containers to ship, no ports to clear, no inventory to insure, and no raw materials to import before value can be created.

The service moves, not the person.

This distinction matters because it eliminates many of the cost layers that make physical exports difficult for Small Island Developing States. Once basic digital infrastructure is in place — reliable electricity, connectivity, and devices — the marginal cost of exporting a unit of digital value approaches zero. A line of code, a marketing strategy, a financial report, or an AI-assisted workflow can be delivered instantly to a client anywhere in the world.

Speed is another advantage.

Physical goods move at the pace of ships, warehouses, and customs processes. Digital services move at the speed of the internet. This allows Caribbean professionals and businesses to compete in real time with firms in much larger economies — responding to clients, collaborating across time zones, and delivering value without delay.

Perhaps most importantly, digital skills scale at the individual level.

A single person with a valuable skill can become an exporter without waiting for factory investment, government incentives, or large-scale infrastructure projects. This makes skills exports uniquely suited to small economies, where rapid job creation and income diversification are essential.

There is also a foreign exchange advantage that often goes unnoticed.

Digital services are typically paid for in USD or other hard currencies. Unlike many manufacturing operations, they do not require large volumes of imported inputs. This means a higher share of earnings remains as net foreign exchange rather than being immediately spent on raw materials, fuel, or logistics.

In simple terms, skills exports allow more USD to stay with individuals and businesses.

Another critical benefit is resilience.

During global shocks — pandemics, climate events, or supply-chain disruptions — physical trade is often the first to stall. Digital services, by contrast, tend to remain active or even expand, as companies look to remote teams, automation support, and digital operations to maintain continuity. This makes skills-based exports a stabilizing force rather than a fragile one.

None of this suggests that digital skills are effortless or guaranteed. They require learning, discipline, and continuous adaptation. But from an economic design perspective, they offer something rare for Caribbean economies: a path to foreign exchange generation that is fast to deploy, low in friction, and accessible at scale.

For Small Island Developing States navigating 2026 and beyond, that combination is not optional — it is essential.

With this foundation in place, the next step is understanding which digital skills actually generate foreign exchange today, and how Caribbean professionals can position themselves for global demand.

5. Global Proof: How Countries Scaled by Exporting Skills

The idea that skills and digital services can drive national foreign exchange growth is not theoretical. It has already been proven — repeatedly — by countries that faced constraints similar to those confronting the Caribbean today.

India, the Philippines, and Estonia did not abandon traditional industries to pursue digital services. Instead, they recognized a simple truth early: skills exports scale faster, travel farther, and generate foreign exchange with far less friction than physical goods. Each country approached this shift differently, but the outcome was the same — global relevance without geographic advantage.

India: Building a Services Engine Before Perfect Infrastructure

India’s rise as a global technology and services powerhouse did not begin with world-class roads, ports, or factories. It began with a strategic decision to treat services exports as a national priority.

Rather than attempting to overhaul its entire manufacturing base, India carved out regulatory and economic space for software and IT-enabled services. Special policy zones reduced bureaucracy, lowered taxes on export earnings, and allowed technology firms to import equipment with minimal friction. This created an environment where skills — not physical infrastructure — became the primary export.

What started as basic coding and back-office work evolved over time into high-value research, product development, and global capability centers serving multinational companies. The lesson for the Caribbean is not scale of population, but sequencing: India did not wait to be “ready” before exporting skills. It used skills exports to accelerate readiness.

Philippines: From Call Centers to Knowledge Work

The Philippines offers one of the closest parallels to the Caribbean. It is an archipelago, culturally aligned with Western markets, and historically dependent on remittances and overseas employment.

Its initial entry point into the global services economy was business process outsourcing — call centers and customer support. But crucially, the country did not stop there. As automation and AI began to threaten low-value voice work, both the private sector and government pushed deliberately into higher-skill services: medical billing, legal support, finance operations, creative production, and analytics.

This progression — often described as “voice to value” — allowed the Philippines to retain foreign exchange growth even as the nature of work changed. The takeaway for Caribbean economies is: skills exports are not static. Entry-level services create pathways to more specialized, higher-income work if reskilling is intentional.

Estonia: Small Size as a Digital Advantage

Estonia demonstrates that population size is not a barrier — it can be an advantage.

With a population comparable to Trinidad and Tobago, Estonia understood early that it could not compete on manufacturing volume. Instead, it focused on building a fully digital state. Digital literacy was treated as a core national skill. Government services were moved online. Business formation, taxation, and compliance became frictionless.

Estonia then went a step further by exporting its digital infrastructure through e-Residency, allowing non-residents to establish and operate businesses within its system. This decoupled economic participation from physical presence and turned governance itself into an export.

The lesson for the Caribbean is profound: digital systems can attract foreign exchange without requiring people to migrate or factories to be built. Efficiency, trust, and ease of doing business become competitive assets.

The Common Thread

Despite their differences, these countries share several traits:

- They prioritized human capital over physical capital

- They reduced friction for services exports before perfecting everything else

- They treated skills as strategic economic assets, not individual career choices

- They accepted that traditional sectors would remain — but would not scale fast enough alone

Most importantly, none of these countries waited for permission from global markets. They adapted to how value was already moving.

For the Caribbean, the relevance is undeniable.

The constraints faced by Small Island Developing States — distance, scale, import dependence, and vulnerability to shocks — are exactly the conditions under which skills-based exports outperform physical goods. The global playbook already exists. The remaining question is whether the Caribbean chooses to apply it deliberately, or continues to rely on models that have reached their limits.

That brings us to the next critical step: identifying which skills and fields are actually generating foreign exchange in 2026, and how Caribbean professionals can position themselves to meet that demand.

6. The Skills That Generate Forex in 2026 (What to Learn and Why)

One of the biggest mistakes people make when they hear “learn digital skills” is assuming it means everything and nothing at the same time.

That’s not helpful.

The goal in 2026 is not to chase trends or collect random certificates.

The goal is to align yourself with where global demand already exists — and where companies are actively paying for skills in USD.

Two global signals matter most here:

Together, they show a clear pattern:

work is becoming skills-based, project-based, and location-independent.

6.1 The Shift to a Skills-Based Global Economy

Across industries, employers are moving away from credentials as proxies for capability.

Degrees still matter in some fields — but they are no longer the default filter.

What now matters more is:

- demonstrable skill

- applied experience

- the ability to deliver outcomes remotely

According to the WEF, many of the fastest-growing roles globally are:

- new or hybrid roles

- digitally enabled

- built around problem-solving, analysis, coordination, and human judgment alongside AI

Coursera’s data reinforces this by showing that micro-credentials, professional certificates, and portfolios are increasingly sufficient to unlock employment and contract work — especially for remote roles.

This is critical for the Caribbean.

Long education cycles delay income.

Targeted upskilling accelerates it.

And because much of this work is remote and project-based, location is no longer the limiting factor.

6.2 High-Value Skill Clusters That Generate USD in 2026

Below are specific skill clusters and roles identified in the WEF and Coursera research that are already generating foreign exchange — and are realistically accessible to Caribbean professionals.

These are not hypothetical jobs.

These are roles companies are hiring for now.

AI & Data Support Roles

(Fast-growing, accessible entry points into the AI economy)

AI is not eliminating work — it is reshaping it.

While advanced AI research roles require deep technical backgrounds, the fastest growth is happening in support, oversight, and applied roles that sit alongside AI systems.

Key roles include:

- Prompt Engineer / AI Workflow Designer

Designing effective prompts, automations, and workflows for generative AI tools used by businesses. - Data Labeling & Analytics Support

Preparing, cleaning, and interpreting data used to train and refine AI systems. - AI Content Moderation & Quality Review

Ensuring AI outputs meet ethical, cultural, and accuracy standards — an area where English fluency and cultural nuance are critical. - Model Evaluation & Testing

Assessing AI outputs for bias, errors, or performance gaps.

Why this works for the Caribbean:

- Strong English comprehension

- Cultural alignment with Western markets

- Low infrastructure requirements

- Rapid upskilling pathways

Digital & Technical Services

(Core infrastructure of the global digital economy)

These roles remain among the strongest generators of USD income globally.

Key roles include:

- Software Developer / Web Developer (Nearshore Advantage)

Front-end, back-end, and full-stack development for US and global companies. - Cybersecurity Analyst & Compliance Support

Monitoring systems, conducting audits, and supporting regulatory compliance. - Cloud & Systems Support Specialist

Managing cloud infrastructure, SaaS tools, and digital operations.

Why this works for the Caribbean:

- Nearshore time-zone alignment with North America

- High demand relative to supply

- Remote-first by default

- Strong long-term earning potential

Specialized Virtual Services

(High-trust, recurring work that companies outsource globally)

These are roles that require accuracy, confidentiality, and familiarity with Western systems — not physical presence.

Key roles include:

- Medical Billing & Health Administration

Supporting US healthcare providers with billing, coding, and administrative processes. - Legal Transcription & Compliance Support

Assisting law firms with documentation, research, and regulatory processes. - Financial Operations & Bookkeeping

Managing accounts, reconciliations, reporting, and operational finance.

Why this works for the Caribbean:

- English proficiency

- Familiarity with Western systems

- Stable, recurring income models

- Lower competition than generic VA work

Project & Operations Management

(Coordination roles that keep distributed teams running)

As work becomes more remote, companies need people who can organize complexity.

Key roles include:

- Agile / Scrum Project Manager

- Remote Team Coordinator

- Product Operations Manager

These roles sit between strategy and execution — and are difficult to automate.

Why this works for the Caribbean:

- Strong communication skills

- Time-zone compatibility

- Leadership and coordination strengths

- Mid-to-high income potential without deep technical coding

Creative & Digital Product Work

(Where creativity meets commercial outcomes)

Creative work has shifted from “nice to have” to revenue-critical.

Key roles include:

- UX/UI Designer

- Digital Brand Strategist

- Content Strategist & Producer

These roles focus on:

- user experience

- conversion

- messaging

- product positioning

Why this works for the Caribbean:

- Strong creative culture

- Global demand for differentiation

- Portfolio-driven entry paths

- Freelance and agency opportunities

The Key Insight (This Matters)

These are skills that generate USD without requiring relocation.

They:

- export cleanly

- scale at the individual level

- require little physical infrastructure

- convert learning directly into income

But here’s the reality most articles avoid:

Not everyone should pursue the same skills.

Your ideal path depends on:

- how quickly you need income

- how much time and money you can invest in retooling

- your existing experience

- the lifestyle you want (freelance, contract, full-time, agency, hybrid)

That’s why random upskilling fails.

Choosing the Right Skill Path (And Avoiding Costly Mistakes)

The WEF and Coursera outline what’s in demand —

but they cannot tell you what’s right for you.

That decision requires:

- aligning skills with income goals

- matching learning paths to your financial reality

- accounting for your lifestyle constraints

- avoiding dead-end or oversaturated paths

To help with this, I built a structured workshop designed specifically for people navigating this transition:

👉 Feeling Stuck? Use This Tool to Find Your Next Career Path

The workshop walks you through:

- evaluating viable skill paths

- choosing based on income timelines

- matching skills to lifestyle and constraints

- creating a practical roadmap tailored to your situation

Because the goal isn’t to learn everything.

The goal is to learn the right thing, at the right time, for the right reason.

And in 2026, that clarity is worth more than any single certificate.

7. Clearing the Confusion: “But We Can’t Get Paid”

At this stage, a familiar objection usually surfaces:

“This all sounds good, but people in the Caribbean can’t actually get paid.”

This belief is common — and it’s incorrect.

The issue isn’t opportunity.

It’s a misunderstanding of where the real friction exists.

To move forward, we need to separate three things that are often incorrectly treated as one:

Generating income ≠ Receiving payment ≠ Accessing and using foreign exchange

They are not the same system.

Generating Income Is Not the Problem

Caribbean professionals are already earning income from international clients — and I know this firsthand.

Since 2017, I’ve worked with companies across the Caribbean, North America, and as far as China, delivering digital services remotely while living in the region. Every one of those clients paid in USD. Receiving international payments was never the challenge.

Over the years, I’ve been paid through:

- PayPal

- regional processors like WiPay

- traditional wire transfers directly into my bank accounts

Those payments arrived consistently, without drama or disruption.

Remote work and digital services are not theoretical concepts in the Caribbean. They’ve been part of the global labor market for years — and Caribbean professionals have been participating in it successfully.

If income generation were the issue, this kind of work simply wouldn’t exist.

If international clients couldn’t pay Caribbean professionals, the transactions wouldn’t keep happening.

The reality is this:

earning and receiving USD is already possible — and has been for a long time.

The confusion arises later, when it comes time to use that foreign exchange within local systems.

And that distinction is where the real conversation needs to be focused.

The frustration most people experience doesn’t happen at the point of payment —

It happens after the money arrives.

The Real Bottleneck: Accessing and Using USD Locally (Trinidad Specific)

This is where confusion sets in.

Once foreign exchange enters the local banking system, it often encounters:

- conversion requirements

- withdrawal and spending limits

- delays from correspondent banking

- restrictions on card usage

This creates the illusion that “we can’t get paid,” when the real issue is how foreign exchange is accessed and used locally.

That distinction matters, because it changes the strategy entirely.

The problem is not:

- global demand

- skill relevance

- payment capability

The problem is local currency infrastructure and controls.

Designing Around the System (Not Waiting on It)

Once this is understood, the question changes.

Instead of asking:

“Can I get paid?”

The real question becomes:

“How do I structure my income and payment setup so it works despite local constraints?”

Many Caribbean professionals have already done this by using a combination of:

- international payment platforms

- foreign-based accounts

- regional processors

- digital invoicing tools

- crypto cards like Redotpay

To help clarify the options, I’ve broken these pathways down in detail:

- Opening a US-based bank account (from Trinidad & Tobago):

👉 https://keronrose.com/how-to-open-a-us-bank-account-from-trinidad-and-tobago/ - Getting paid via PayPal in Trinidad & Tobago:

👉 https://keronrose.com/getting-paid-with-paypal-in-trinidad-and-tobago/ - All the practical ways Caribbean professionals get paid by international clients:

👉 https://keronrose.com/are-you-struggling-to-get-paid-by-international-clients-in-the-caribbean/

These are not theoretical options — they are the same structures people across the region are using right now. I personally use all of the methods to get paid that I’ve listed out in the above guides.

Why This Mental Shift Is Critical in 2026

When people believe they “can’t get paid,” they hesitate.

They delay learning new skills.

They wait for policy changes.

They assume migration is the only solution.

None of that is necessary.

Understanding where the friction actually exists allows you to:

- earn globally

- receive payments reliably

- design systems that work within current constraints

The constraint is real — but it is not a dead end.

Once that clarity is in place, the next step becomes practical:

understanding how Caribbean professionals are actually receiving payments in 2026, and which tools and setups make the most sense depending on their situation.

That’s where we go next.

8. How Caribbean Professionals Structure Payment Systems in 2026

Once you understand that earning and receiving international income is possible, the real work begins: designing a payment system that fits how you earn, spend, and store money.

In 2026, successful Caribbean professionals are not asking, “Which platform should I use?”

They are asking, “How do I build a setup that gives me flexibility, redundancy, and control?”

This shift in thinking is critical.

From Single Accounts to Payment Stacks

Most people start with a single payment method and treat it as a permanent solution. That approach usually fails once income grows or becomes more complex.

Instead, professionals now operate with payment stacks — a combination of tools, each serving a specific role.

A typical stack separates:

- client-facing payment collection

- temporary USD holding

- local and international spending

- accounting and record-keeping

No single platform does all of this well. The strength comes from how the tools work together.

Making It Easy for Clients to Pay

The first priority in any payment system is reducing friction for the client, not for yourself.

Professionals who work internationally ensure that:

- clients can pay using familiar methods

- payments do not require special approvals or explanations

- invoices and checkout flows look professional and credible

If a client has to “figure out” how to pay you, you’ve already introduced risk into the transaction.

Separating Earning from Spending

A common mistake is trying to earn, hold, and spend money from the same place.

Experienced professionals separate these functions deliberately:

- one layer for collecting income

- another for holding or allocating funds

- another for spending, subscriptions, or transfers

This separation creates:

- better cash-flow control

- reduced exposure to sudden restrictions

- clearer visibility over income streams

It also makes it easier to adapt when rules or limits change.

Designing for Redundancy, Not Perfection

In constrained environments, redundancy is a feature, not a weakness.

Professionals avoid relying on a single bank, card, or platform. Instead, they design systems where:

- if one pathway slows down, another still functions

- income is not locked behind a single point of failure

- operational continuity is maintained

This mindset comes from experience — not theory.

Matching Your Payment Setup to How You Work

There is no universal payment architecture.

The right structure depends on:

- whether you’re freelance, contract, or running a business

- how often you invoice

- the size and predictability of payments

- where your expenses actually occur

A consultant paid monthly will structure payments differently from a creative paid per project. A solopreneur running subscriptions will differ from a remote employee.

The goal is alignment — not copying someone else’s setup.

The Real Advantage of a Well-Designed System

When payment systems are designed intentionally, professionals gain:

- smoother cash flow

- reduced stress around access

- faster decision-making

- more confidence in scaling their work

At that point, payments stop being a constant concern and become infrastructure — something that quietly supports growth rather than blocking it.

With payment systems in place, the focus can finally shift to what matters most:

how earning globally changes the way people can live, work, and plan their lives while staying rooted in the Caribbean.

That’s where we go next.

9. Living in the Caribbean, Earning Globally

For decades, opportunity in the Caribbean followed a familiar path:

if you wanted to earn more, you had to leave.

Higher incomes were tied to migration. Career growth often meant relocation. Staying behind was framed as a limitation rather than a choice.

That relationship between place and opportunity has now changed.

Digital skills and global service work have decoupled where you live from who you work for. For the first time at scale, Caribbean professionals can earn internationally while remaining rooted in the region — not as a compromise, but as a strategic decision.

This shift is already happening.

When income is generated globally, individuals gain options that were previously unavailable:

- earning in stronger currencies

- reducing dependence on local wage ceilings

- managing cost of living more intentionally

- reinvesting income into families, communities, and businesses

The result is not just higher income — it is greater control.

Living locally while earning globally allows people to:

- stay connected to family and culture

- avoid the social and emotional cost of migration

- choose mobility rather than being forced into it

- design lives that balance work, health, and community

This is an important distinction.

Migration is no longer the default requirement for economic advancement.

It becomes one option among many.

For small island economies, this matters deeply. When people can generate foreign exchange without leaving, the region benefits from:

- retained talent

- stronger local spending

- more resilient households

- diversified sources of USD inflows

The economic impact is quiet but powerful.

Instead of relying solely on remittances sent back by citizens abroad, skills-based exports allow foreign exchange to be earned at home, distributed across individuals rather than concentrated in a few industries.

This is not about rejecting travel or global experience. Many people will still choose to move, work abroad, or live nomadically. The difference is choice.

When skills and systems are in place, people are no longer migrating out of necessity.

They are making deliberate decisions based on opportunity, lifestyle, and values.

That shift — from forced movement to intentional design — represents one of the most meaningful changes in how Caribbean professionals can approach work and life in 2026 and beyond.

With this possibility comes responsibility:

to choose skills deliberately, to plan strategically, and to avoid drifting into the next phase unprepared.

That is where the next section begins.

10. From Skill Confusion to Strategic Direction

One of the biggest risks in 2026 isn’t a lack of opportunity — it’s misdirected effort.

Once people accept that digital skills can generate foreign exchange, the next trap is trying to learn everything at once. Courses are started and abandoned. Certifications pile up without translating into income. Time, money, and energy are spent — often with little clarity on whether the chosen path was viable in the first place.

This is where random upskilling leads to burnout.

Strategic selection matters.

Not every in-demand skill is right for every person. The “best” skill depends on factors most advice ignores:

- how quickly income is needed

- how much time and money can realistically be invested in retooling

- existing experience and transferable strengths

- tolerance for uncertainty and learning curves

- the kind of lifestyle someone wants to sustain

Without a framework, people default to trends or copy what worked for someone else — often with disappointing results.

What’s needed is not more information, but better decision-making.

That’s why I built a structured workshop designed to help people move from uncertainty to clarity:

👉 Feeling Stuck? Use This Tool to Find Your Next Career Path

https://keronrose.com/feeling-stuck-use-this-tool-to-find-your-next-career-path/

The workshop is not about chasing hype or listing every possible skill. It walks participants through a process that:

- aligns skills with realistic income potential

- accounts for personal constraints and timelines

- filters options based on effort-to-reward trade-offs

- produces a clear, personalized roadmap

It acts as a bridge between interest and execution — helping people avoid costly detours and focus their energy where it has the highest chance of return.

In an environment where time, money, and attention are limited, clarity becomes a competitive advantage.

And in 2026, the people who win won’t be the ones who know the most —

they’ll be the ones who choose well and execute deliberately.

11. Final Word: The Most Scalable Export the Caribbean Has

The Caribbean’s challenge has never been a lack of talent.

Across the region, people are skilled, adaptable, creative, and globally competitive. What has been missing is not ability — it is systems designed for a modern, digital export economy.

For decades, economic strategy has focused on moving physical goods and people. Factories, ports, tourism arrivals, and migration were treated as the primary paths to foreign exchange. Those models delivered value, but they also reached their limits — especially for small, import-dependent economies facing rising costs and global uncertainty.

What has changed is not the ambition of Caribbean people.

What has changed is how value moves in the global economy.

Digital skills allow individuals to export value instantly, at low cost, and at scale. They bypass many of the structural frictions that small island states face and turn people themselves into productive, resilient sources of foreign exchange.

When citizens earn globally while living locally, the impact compounds:

- households become more resilient

- communities retain talent

- foreign exchange flows diversify

- dependency on a few industries decreases

This is not about replacing tourism, manufacturing, or energy.

It is about adding the most scalable export available to the Caribbean’s economic toolkit.

One that doesn’t require ships, ports, or massive capital investment.

One that can be built person by person, skill by skill.

In 2026, the most powerful way to generate foreign exchange isn’t through more goods or more tourists —

it’s through people exporting skills, earning globally, and living locally.

That future is already within reach.

The question now is how deliberately we choose to build it.

Excellent article. You gave great insight into how Caribbean citizens can earn forex while staying in the region. Looking forward for more articles.

very encouraging and informative do you have articles on creating and selling digital product